The name of Home originates from an Old English word Hôm, which in its dative form described a place on an hilly outcrop or height. The situation of Hume Castle readily explains this origin and through the ages it has been spelt in several different ways, appearing in documents over the past eight centuries in up to 8 various spellings. Always pronounced Hume, the barony, castle and village retained the Home spelling until the end of the 18th century; many families over the centuries have switched to the Hume version to avoid confusion of pronounciation for those living away from the Borders, whilst others have retained the Home spelling.

Hume Castle is the location from which the Home/Hume Clan takes its name and is situated on a hill some 750 feet above sea level, between Gordon and Kelso, with the small village of Hume beside and below it.

It was, for centuries, arguably the major defensive site in the Eastern section of the Borders, often called the Merse, as it is placed in such a commanding position with views described as the best in the Scottish Borders, sweeping down to the Tweed valley with the Cheviots to the South, past the Eildon Hills to the West and North to the Lammermuirs.

Its history, therefore, is a cross section of both Scottish and English history. No victorious army could afford to risk the recapture of so valuably strategic a position by the enemy and consequently it was frequently burned or destroyed.

The lands of Hume, or Home, were first granted as a dowry to Ada who was the daughter of Patrick, Earl of Dunbar in 1214, when she married her first husband, William de Courtney. He died in about 1217 and two years later married Theobald de Lascelles. This hapless lady became a widow for the second time in 1225. She then married her cousin, William, son of Patrick of Greenlaw. He assumed, in her right, the name of Home. The descent of the Home/Hume family is traced from him.

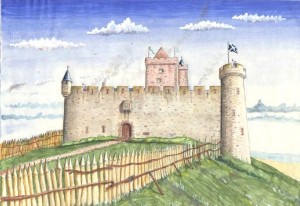

Built upon a natural outcrop of rock, the castle was constructed in a rectangular courtyard plan; a common configuration seen in the Highlands but quite unusual for central and southern Scotland. Successive Lords Home, seated at Hume Castle, were Wardens of the Eastern Marches, policing the Scottish side of the Border, which was less than five miles away. For generations the fortress was alternately in the hands of the English and Scots.

King James II used Hume Castle as his base whilst attempting to destroy Roxburgh Castle in 1460, which was held by the English. He was using cannons imported from Flanders. On 3rd August, one of these cannons, known as ‘the Lion”, exploded and killed the King

Following the disastrous battle of Flodden in 1513, a legend has it that Alexander, the 3rd Lord Home, who, during the battle, had withdrawn his troops from the field after having successfully attacked the English right flank, took possession of the body of King James IV and hid it in a cave adjoining the well at Hume Castle. (During the 19th century a skeleton was found in the medieval well with a chain around his waist. Was this the King? Sadly it disappeared, so we’ll never know.) Whether the legend was true or not, Lord Home was falsely accused of plotting against the infant James V and the Regent Albany. He was tricked into appearing in Edinburgh, arrested and executed, along with his young brother William in 1516.

The Regency installed a French ambassador, Antoines d’Arces, the Chevalier de la Bastie, into Hume Castle as Deputy Governor of the district and the new Warden of the Marches. This act infuriated Lord Home’s kinsman (4th cousin), Sir David Home of Wedderburn, who took fearful revenge and slayed him on the 18th September 1517, displaying his head from a pole in the centre of Duns village.

After many years, having regained his lands and castle, George (another of Alexander’s brothers), now the 4th Lord Home, commanding the Scottish cavalry on the eve of the battle of Pinkie, on the 9th September 1547, was caught in a skirmish with the English. Fighting alongside George was his son and heir Alexander. George was mortally wounded and his son, Alexander, was taken prisoner.

After winning the battle of Pinkie the following day, the English Commander, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset then attacked Hume Castle and found George’s wife Mariota, Lady Home, defending strongly. Somerset threatened to execute her son, Alexander, unless she surrendered, which she did on the 22nd September 1547. The English spent £700 strengthening the defenses under the Governorship of Sir Edward Sutton (who became 4th Baron Dudley), a Commander in Seymour’s army. A year later the now freed Alexander, now the 5th Lord Home, recaptured the castle in December and put the entire English garrison to death, apart from Edward Sutton who was captured and imprisoned.

[Interestingly Edward Sutton’s granddaughter, Mary (1586-1645), became Countess of Home when she married, as his second wife, Alexander 1st Earl of Home (1566-1619) who was of course Alexander the 5th Lord’s son.]

Despite having signed the order for the imprisonment of Mary, Queen of Scots, the 5th Lord Home later became one of her supporters and the Queen enjoyed the hospitality of the castle on her final journey to England, when she was forced to abdicate in 1567. Lord Home joined her loyal garrison at Edinburgh castle, which fell and he was imprisoned. He died two years later. The English then attacked Hume Castle again, taking revenge on Home property.

This fine medieval fortress was mostly destroyed, in February 1651, by bombardment at close range by the parliamentarian (Roundhead) artillery of the foot regiments of Colonel George Fenwick and Colonel Edmund Syler. They were under the orders of Oliver Cromwell as part of his plan to possess or destroy all Scottish border garrisons that could threaten his Parliamentary New Model Army. (Fenwick had just been made Governor of Leith and Edinburgh Castle following their crushing victory over the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar on 3rd September 1650)

Fenwick sent a message to the Governor of Hume Castle, Colonel John Cockburn, warning him of his intentions. Cockburn politely refused to surrender, stating that he did not know who Cromwell was. He sent a further message, in challenging doggerel, to Fenwick:

“I, Willie Wastle

Stand firm in my castle;

And a’ the dogs in your toun

Will no’ pu’ Willie Wastle doun.”

Fenwick did, despite this, succeed in making a breach in the walls and was about to enter when Cockburn arranged a parley. Fenwick agreed that the garrison, along with Cockburn, totalling 78 commanders and men, could leave alive. Captain Collinson and his company then occupied the castle.

In 1745, Government forces held the mostly ruined castle as a check on the Jacobites, led by Charles Edward Stuart the Bonnie Prince Charlie, who had taken Edinburgh almost unopposed.

Following the military defeat of the Jacobite Rising at Culloden in 1746, the castle reverted back to the Home family. It now was the property of the Earls of Marchmont, descendants of a younger branch of the Homes of Wedderburn. Sir Hugh Hume, 3rd Earl of Marchmont, built from the ruins the present castle in 1789. These 18th century walls enclose a much smaller area than that of the old castle. There is still a portion of an original inner wall, perhaps part of the tower, remaining in the centre of the courtyard. The exaggerated size of the crenellations was to make it a distinctive castle when viewed from Marchmont House, the Earl’s new seat built in 1750 about 8 miles to the north east.

The Earldom of Marchmont fell dormant on Hugh’s death in 1794 and from that time, the castle has played various roles.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the castle triggered what is known as “The Great Alarm” of 1804. News of any impending French invasion was to be spread across the country by lighting beacons on the area’s vantage points. On January 31st the duty watch sergeant at Hume Castle saw a distant fire, some say from Dirrington Great Law to the north and others the Cheviots to the south. Mistaking it for a lit beacon, the watch lit their fire. Neighbouring beacons, such as those on North Eildon Hill and Crumhaughhill, were quickly lit and 3000 volunteers turned out in defense. The following day the mistake was confirmed. There was no invasion. Happily, due to the speedy response, a dinner party was held to celebrate.

The castle was acquired by the State in 1929 lying within the Department of Agriculture for Scotland.

In 1985 the Berwickshire Civic Society initiated a restoration programme, funded by the Scottish Office.

In 2006 it was bought by the Hume Castle Preservation Trust, a sister organisation of the Clan Home Association.